12 months ago I took a leap and decided to freelance. One year later, these are some of the things I talk about when people ask me what it’s like.

#1 Managing your own hours is a superpower.

The ability to choose your hours, in terms of when and how many, does incredible things to your happiness. Early on I decided to work no more than four days a week in big agencies. This created time to work on other projects (paid and unpaid), chase new ones or just enjoy a sleep in on a Friday.

The changing cadence also keeps you interested and interesting. I did everything from a three month contract to one project which was literally half an hour. You can choose to focus on one big thing, or juggle ten smaller ones. The latter meant I could do a 15km run in March, which was only possible because I dropped everything at 11am and went for a jog when I wanted to.

You do need to be buttoned down on your calendar management. Even then sometimes things don’t always line up. I’ve accepted a few days of work, then 10 minutes later had to turn down a bigger gig because you’re already committed. Sometimes work just disappears too – I was three days into a month-long pitch which got pushed out by months. Annoying when you’ve already turned down two other jobs to be there.

But that’s freelancing life. The contracts always favour the employer (but you only get them from bigger agencies). It’s why they pay you more.

Despite being the master of my own calendar, my grand plans to work on side projects failed miserably. It’s rather easy to take on more paid work or spend time meeting people for coffee while passion projects collect dust.

#2 Choosing who you work with and what you work on, helps navigate your career.

Freelancing allows you to pick the types of brands, agencies and people you work with. And the projects you want to invest time in.

This year I worked with big agencies, small agencies, entrepreneurs, starts up and consulting my own clients. But you also have flexibility in the role you play in the work you say yes to.

You can reinvent your job title (and yourself) with every new project, pushing into uncomfortable spaces to play around with. One of my favourite adventures this year was developing the marketing strategy to launch a gluten-free brewery. Not quite my heartland of creative strategy, but a category close to my stomach, and a rewarding project which has become ongoing. Throughout the year I picked up everything from writing content strategies through to delivering full service campaigns white labelling freelance creatives under Pigs Don’t Fly.

You get to flirt around and try on different hats. One year later I have a much closer idea of where the intersection is between what I like doing, what I’m good at, and where the money is.

#3 The market for freelance strategists is good right now.

I am fortunate. I have a good-sized network built from nearly a decade in two large agencies. This created most of my opportunities.

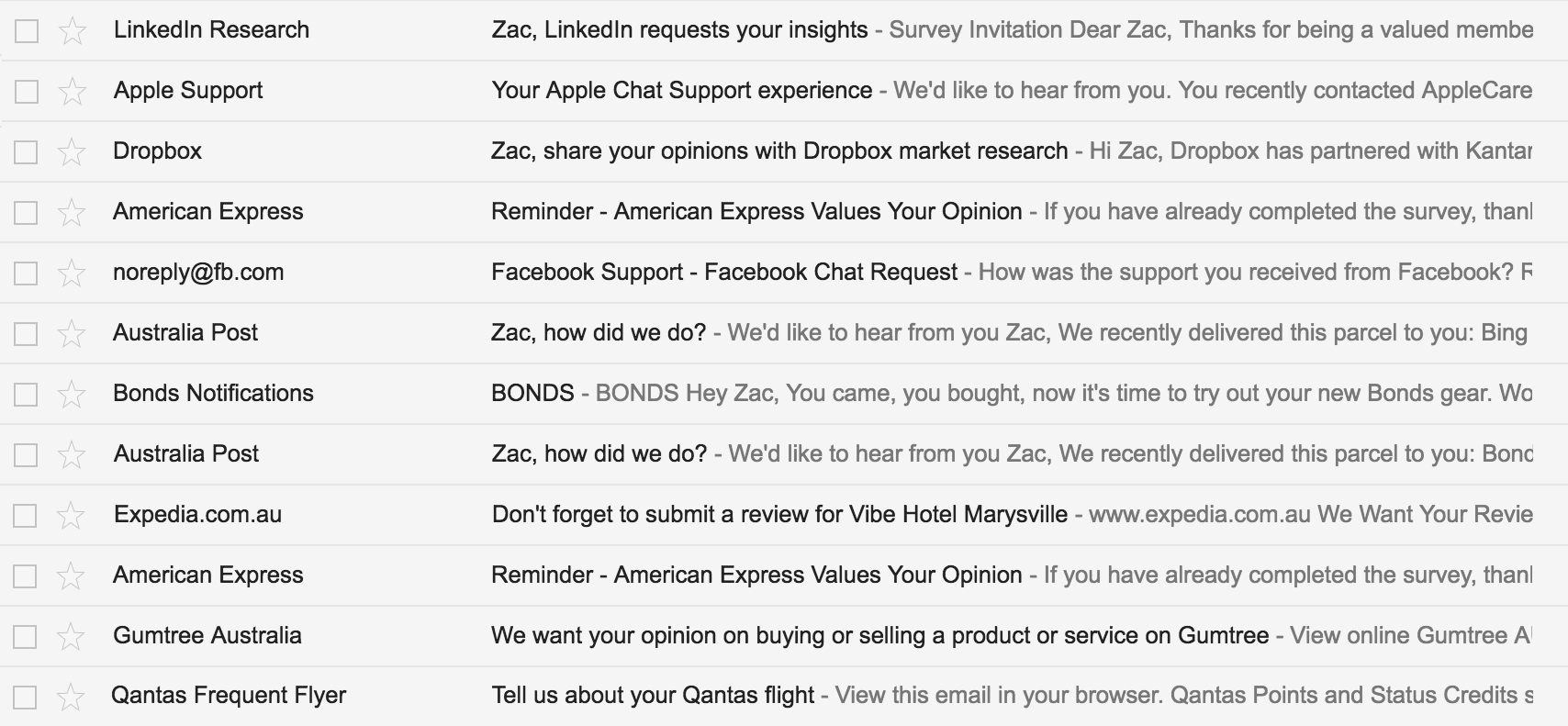

I also have somewhat of an audience (you suckers) – writing here and on places like Mumbrella helps keep me top of mind as a potential resource. In two cases it also opened new doors which turned into work.

I also realise I fell into an attractive role. I’d suggest large parts of my success aren’t because of how good I am, but rather a lack of freelancer planners in Melbourne. If I was a designer, I’m not sure if I’d be writing such a romantic post.

I also managed the whole year without using a recruiter. They eat a decent piece of your day rate.

Without being arrogant, honestly my biggest challenge was learning to say no to work. Especially early when I wasn’t sure what my income would average out to. Even still it’s bloody challenging turning people down – knowing the opportunity cost and wondering if you can find time after hours to make it happen. Even to this day I wonder if I got lucky and am still in a honeymoon period, and should be making more hay while it shines.

With the ebbs and flows you do sometimes find everything crashes at once. I’m doing more weekend work now than in my permanent life (which my former colleagues will tell you wasn’t much). Other times it’s quieter than you want it to be. I got some advice to make the most of those days – get out of Melbourne and spend time at your beach house. If only I had a beach house.

#4 The money is great, but you have to learn how to earn it.

The money is really good. I finished the year 36% up on my old salary.

But it takes time to learn what you’re worth. And even longer to be confident enough to ask for it. I sold myself short for at least my first two gigs. To this day still need to stop negotiating myself down unnecessarily, often before the other person has even responded. Never has your imposter syndrome screamed louder than when someone looks you in the eye and asks your day rate. At least these conversations happen frequently, so you get good at it fast. You learn to throw your number out there and then stop talking.

Eventually I worked out to be stupid and arrogant enough to ask for what I thought was a stupidly high day rate. And they said yes. And keep saying yes. I do wonder how this dance impacts men versus women.

If you’re thinking of freelancing, my advice is to add at least 25% on top of what you think you can get. Push as far as you are comfortable and then a little more. Remember you are covering down time, your own expenses, equipment, annual leave, sick leave, training, work beers, etc.

I unsuccessfully gambled with remuneration. Twice on pitches I cut my rate in half, adding 50% on top if we won. Neither paid off (although I did help win other pitches!). I also did one job for cryptocurrency – right now it’s down 60%. This year I’ll stick to cash.

Along with good calendar skills, you also need to run a tight ship with your bookkeeping. I manage mine through an unnecessarily detailed Google Sheet, which works for me. I also manage my own quarterly tax statements (it’s easier than you think). Paying your own superannuation and tax annually does take discipline – eventually I created a separate account and moved the money out of sight.

The cliché of chasing invoices actually wasn’t too bad. The big agencies sometimes drag their feet, but 90% of my invoices would have been paid within three weeks.

#5 All big agencies are the same, but some have better culture.

Most agencies look and smell the same. The people who work there are kinda the same too. They tend to dislike their clients, work longer-than-healthy hours and think the chaos is unique to their agency. But they are good people who come to work every day wanting to do good work.

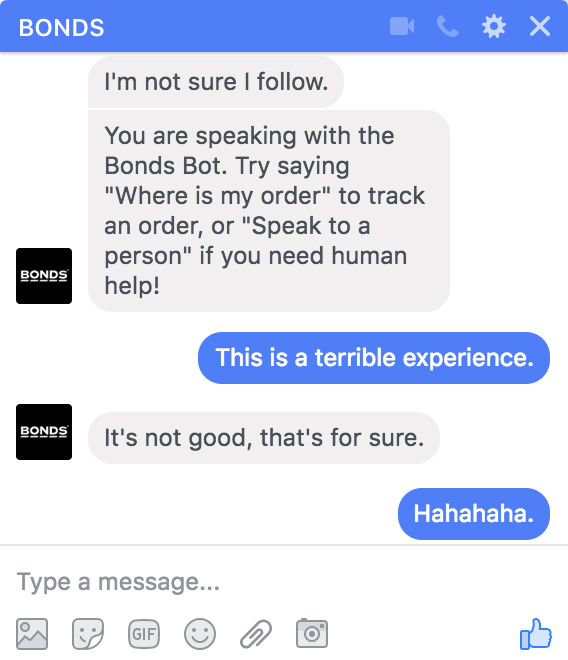

Culture is distinctive though. You notice it particularly as a freelancer where you see lots of it fast. It’s most evident in how much an agency encourages you to get among it or put your head down and work. It’s a bit like gravity – you can feel it immediately but it’s harder to see the cause. Sometimes you can tell in the first ten minutes, particularly when someone in IT tells you they don’t allow freelancers on the WiFi.

I didn’t realise it until this year, but in my permanent life I was spoiled with access to coffee machines. Seriously agencies, sort this out!

#6 It’s not all fun and games.

Not having a work crew sucks. I miss the daily banter. Having worked in bigger planning teams in the past, it’s also tough not having another strategist to throw something around with.

Working from home for too many days in a row isn’t heathy either. Especially in winter. For my next stint at home I’m going to find a temporary coworking space.

Unfortunately you rarely get to see work through. You come in, do your piece, and you’re out. You don’t often get the opportunity to nurture and help ideas grow. Last week I saw an ad for a strategy I wrote six months ago which I thought got killed. It wasn’t a very good ad.

It’s also challenging not working toward something bigger. Freelancing is constantly short term. You need to be comfortable with not knowing what’s happening next week, and not relying on fulfilment from big career-defining moments which take time to build up to.

You’ll be tempted into permanent work. I had a few full time and part time offers, one including equity. But while it’s not all sunshine, there’s still plenty to love because…

#7 Freelancing is awesome.

You meet heaps of people. You learn a lot, fast. You rapidly get the opportunity to steal elements you like and learn to avoid those you don’t.

Critically, you get a license to be brutal with recommendations. There’s no client baggage or incentives to get involved in politics. It sounds counterintuitive for a strategist to say, but not being committed long term allows you to approach work with an attitude of “My contract finishes tomorrow, so I don’t care what you decide – but this is the right recommendation”.

My work this year has been better because I was more empowered to take a step back and challenge the client, rather than just answering them.

And finally, I worked out that agencies only bring in freelancers when they need help. So if you can be even a little bit helpful, everyone is bloody happy.

– – –

If you’re thinking about freelancing in advertising, shoot me your questions. I’d love to share my invoice templates, advice on day rates or tell you which agencies have craft beer in their fridges.

Posted by Zac Martin