18 June 2017 Economic Thinking in the War on Waste

ABC’s War on Waste is a fantastic series that explores how we’re fucking up the environment. Once you get over your guilt, it prompts a lot of conversation on how we need to change to reduce our impact.

It’s even more interesting through the lens of behavioural economics.

One of the show’s major focuses is food wastage. Annually we throw away $8 billion of food, having produced enough to feed 60 million people (nearly two and half times our population). And it’s a huge problem, not just in wasted resources for production but in disposal. When food rots in landfill with other organic matter it releases a greenhouse gas 25 times more potent than the carbon dioxide from car exhaust.

It’s not just household behaviour to blame, in many cases food becomes waste before it leaves the farm. War on Waste hones in on bananas, our number one selling supermarket product with five million purchased daily. That’s a lot of bananas.

The banana grower highlighted in the show, the third largest in Australia, produces 1.4 million boxes a year. In some cases up to 40% can be put straight into landfill. Again, that’s a lot of bananas.

Why? It’s not because they’re bad.

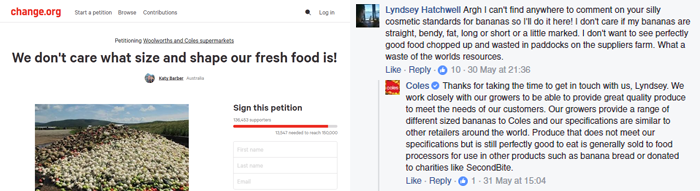

Our supermarkets have strict cosmetic standards on what is acceptable. Bananas can’t be too long or too short. They can’t be too fat or too thin. Too marked or too ugly. Craig Reucassel, the host of the show, gets particularly frustrated that one of type of straight banana can be thrown away because it’s too bent, while another bent breed can be too straight. That’s really fucking bananas.

These, he points out, are arbitrary rules defined by the supermarkets.

The supermarkets blame consumers (of course!). And while they make token efforts through initiatives such as Woolworth’s Odd Bunch – they state it’s consumer demand that drives decisions on what makes a banana too straight or too bent.

Thankfully, a generation of slacktivists responded (I’m not actually that skeptical, it’s a really good thing people give a shit). 136,000 supporters signed a petition announcing we don’t care what size and shape our fresh food is. And those poor Community Managers running the Facebook pages for Woolworths and Coles have been flooded with messages.

But I don’t believe it’s that simple. Or that people realise the potential consequences of their actions. Inspired by years of the Freakonomics podcast, I started thinking how this could actually play out.

Sometimes we appear to be doing more good than we actually are. And in some cases we make it worse (see the Cobra Effect).

Take the recent changes for first home buyers here in Australia. In an attempt to increase home affordability, the government has added incentives for people to buy their first property. But when you increase the market’s buying power, demand goes up. And homes will be more expensive, not less.

Humans are also really good at exploiting systems, which is why you’ll often see properties sold for $600,001 – $1 over the threshold for stamp duty savings.

This is why we need economist-thinking on what happens if Coles and Woolies relax their cosmetic standards. I’m by no means educated enough to think this out a loud, but sometimes that’s what blogs are good for.

If we relax our cosmetic standards for fruit, more bananas become available. Less bananas leave the farm for landfill and instead end up on supermarket shelves.

But demand won’t increase overnight. Australian’s aren’t suddenly going to start eating 40% more bananas.

Allowing more bananas through the system will make farmers more efficient, but the supermarkets don’t have a need for the surplus bananas.

With 60% of the land and resources now supplying 100% of Australia’s banana needs, it opens opportunities for farmers to diversify the remaining 40% into alternative production. Even if the land can be used for something else, it requires capital and knowledge. Not to mention the inefficiencies in managing two different products. I’m no farmer, but I imagine it’s not simple to turn a banana plantation into an apple orchard.

Instead, farmers will lose jobs (and likely farms). If the supermarkets only need six farms to supply them instead of ten, four go out of business. It’s cheaper to deal with fewer suppliers.

That’s a tough outcome for a country who’s been hearing about the struggling farmers for the past decade. But that’s the free market and while we’ll ultimately be better off, there’s hardship to be had in the process.

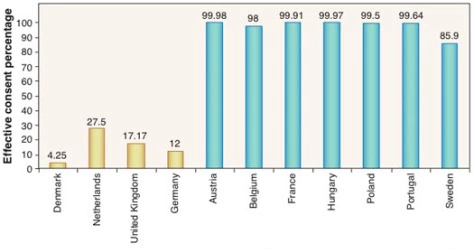

There is another factor: price. You learn in the first week of Economics 101 that an increase in supply lowers price. And there is some evidence to suggest bananas are quite elastic, meaning price movement impacts sales. 2006’s Cyclone Larry saw almost 90% of Australia’s banana supply wiped out, with prices up 500% leading consumers to seek fruit alternatives. But can a 40% demand gap be utilised by dropping the price a dollar per kilo? How many bananas can we eat?

If it happened, it would be a great outcome – particularly if Aussies were to consume in favour of cheaper junk foods. Health, unfortunately, is not really the concern of supermarkets.

The one place there is actually a supply shortage is feeding those in need. But based on the same episode of War on Waste the issue here is not in food donation – it’s logistics and storage which are most problematic (and expensive).

Ultimately if you remove what is essentially a tariff for something to become more efficient, it will be better for the market long term. But it means farmers might lose jobs.

Of course, it’s not really that straight forward. And I’m not nearly clever enough to talk about it as much I have – but I do wonder if 136,000 people who signed the petition thought about its impact.