10 October 2024 Don’t tell them how good you are. Tell them what you’re good for.

Years ago, I was working on Cadbury Favourites. They were coming off their hugely successful ‘What to bring when you’re told not to bring a thing’ campaign. The strategic challenge was; do we double down on the BBQs moment, or do we move onto a different one?

In hindsight, with the benefit of marketing science, the answer is obvious. It’s classic Category Entry Point theory. And we don’t spend nearly enough time thinking about them, and building them.

What are Category Entry Points?

CEP theory was first popularised in How Brands Grow Part 2 (2015), but thanks to the Ehrenberg-Bass Institute’s latest book Better Brand Health (2023) we have an even better understanding of why they matter. One of their key findings being much of brand health tracking isn’t useful, and we should be spending significantly more effort measuring CEPs instead.

What is a CEP? The official definition is “the cues buyers use to access their memories when faced with a buying situation”. Simply – it’s the trigger which brings a brand to mind when you have a need. A fancy way to say occasion.

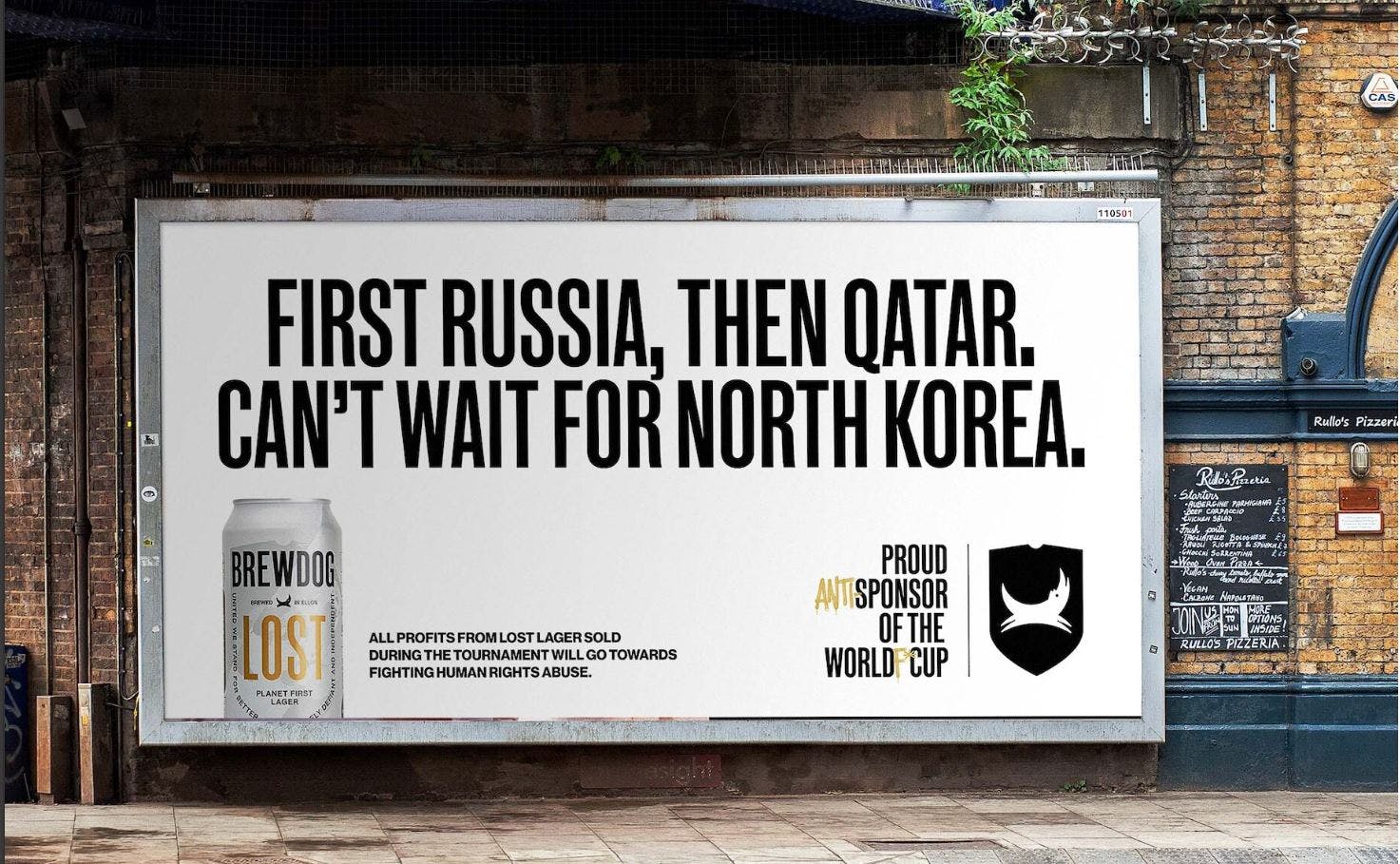

Brands win by linking themselves to these buying situations. Guinness have famously built associations with a range of different CEPs – when in Ireland, when it’s cold, when I’m in a pub with a sticky carpet.

Some brands build them through campaigns, like Aperol Spritz’s annual takeover of the Australian Open. Others build them through their brand platform, like Canadian Club’s multi-Effie-winning platform ‘Over beer?’.

And it all sounds kind of obvious. If I explained to my mum that brands grow by associating themselves with moments when consumers need brands, she would say “no shit”. And yet, we never talk about it.

The more CEPs you own, the more you win.

Your job is to build muscle memory, so when consumers have needs, your brand is a little bit more likely to come to mind first. That’s mental availability – being easily thought in buying situations. If you’re easily thought of, you’re easier to choose.

And the latest marketing science gives us a clear answer to our Cadbury Favourites challenge – bigger brands own more Category Entry Points.

The more occasions you own in the mind of consumer, the more customers you have. And the lower your defection rate. You don’t want to own one occasion; you want to own many.

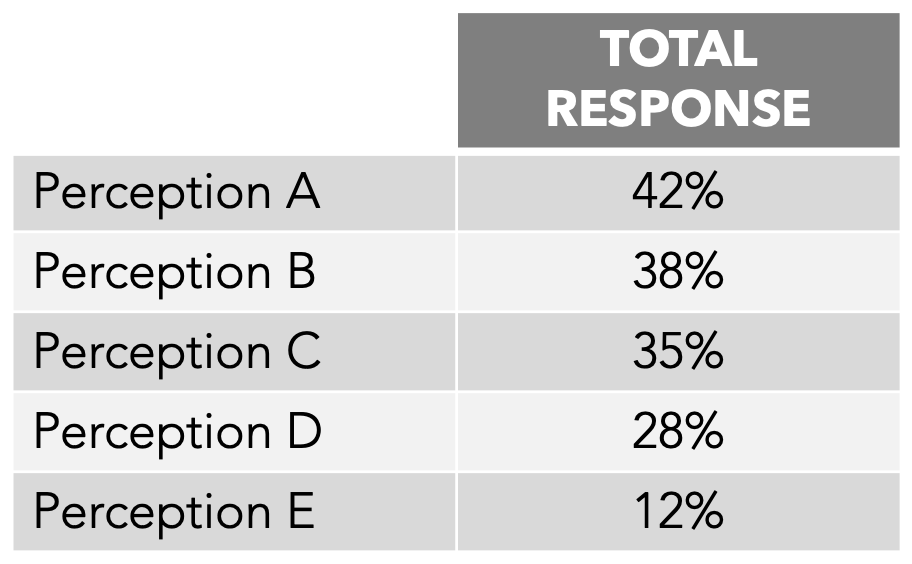

One of the new metrics to come out of Better Brand Health is ‘mental market share’ – your brand’s share of all CEP linkages in a category. As visualised here by Smart Marketing, there is a good correlation between Mental Market Share and Actual Market Share.

Do work which builds associations with one occasion. Then, move onto the next (while also refreshing the first as necessary). Repeat.

The problem with positioning.

The approach might be obvious, yet Category Entry Point theory is counter to how we’ve been thinking about brand growth for more than half a century. The prevailing tool being ‘positioning’ – owning a single position in the mind of a consumer. Philip Kotler first suggested this approach in 1969 with his STP Model – you segment, then you target, then you position.

But CEPs theory says this is wrong.

Jenni Romaniuk, of Ehrenberg-Bass Institute, says “[CEPs are] contrary to how we’re brought up to believe branding works. It’s contrary to this idea of positioning, finding that one thing you can own to be different from everybody.”

Don’t worry about what people think of you, instead worry if they think of you at all.

Don’t tell them how good you are (positioning), tell them what you’re good for (CEPs).

Apple was once famously positioned for creative rebels, with its now largely-absent platform ‘Think Different’. But today, they build the brand through CEPs like devices for remote work, devices for privacy, and devices for accessibility.

This work from Guinness generated a lot of head scratching, with pundits asking “Who would drink a Guinness in summer?” That’s exactly the point! They own winter – their growth comes from owning more buying situations. Perhaps this strategy helped them become UK’s number one beer in 2022 for the first time ever.

Why we’re slow to jump into CEPs

Despite this theory surfacing nearly a decade ago, and some case studies showing incredible growth deploying it, our industry has been slow to adopt. A few reasons why:

Firstly, it challenges conventional tools like the Benefit Ladder. CEPs theory says features and benefits can bugger off, just build associations with category needs instead. But it’s hard to stray away from established frameworks.

Secondly, the ‘differentiation versus distinctiveness’ argument raises its ugly head. KitKat has no functional reason to own having a break, but they do because they’ve been banging on about it for a long time. You don’t need a point of difference; you can own something by owning it.

Thirdly, category needs are often labelled as category generic. But that’s kinda the point – that’s why consumers are entering the category. It’s a strategy that often goes against ‘finding the white space’.

Lastly, CEPs briefs don’t tend to solve a big insightful consumer problem – which is traditionally the point of a planner. Perhaps some self-preservation prevents agencies from writing briefs as simple as “VB is for after you mow the lawn” or “Four’N Twenty is for when you’re watching the footy.” Mark Cichon, from The Commerical Works, asks “What if there is no problem, and your task is simply to communicate how a brand fits into peoples’ lives?”

Think about CEPs on your next brief.

Of course, it’s not the only message to build a brand platform on. Nor is it the only way to write a prop for your next campaign. But Category Entry Points are under-appreciated, under-utilised, and under-understood.

On your next brief, try starting with the occasion. And once you’ve owned that in the minds of consumers, move onto the next one.

Zac Martin is a Planning Director at TBWA\Melbourne. This article was originally published on Mi3 Australia.

Many of us were taught to climb as high as possible when writing briefs, beyond the product’s features to the rational and emotional benefits. While a helpful tool in unpacking the consumer problem, there’s little evidence to suggest the benefit being communicated must be emotional. The

Many of us were taught to climb as high as possible when writing briefs, beyond the product’s features to the rational and emotional benefits. While a helpful tool in unpacking the consumer problem, there’s little evidence to suggest the benefit being communicated must be emotional. The