13 December 2022 The single most important thing is being noticed

Last month, Netflix released Pepsi, Where’s My Jet?, a documentary series on the infamous Harrier Jet consumer-promo-gone-wrong scandal.

It’s a real David and Goliath story. Deep into the Cola Wars of the 90s, Pepsi launches a loyalty program, and jokingly advertises the opportunity to purchase a US$23m military aircraft for 7,000,000 Pepsi Points. One enterprising young man discovers you can buy the required points for just US$700k, and a very public legal battle ensues.

The marketing industry has been quick to criticise Pepsi, suggesting the negative PR back then, and now with the doco, could easily have been avoided by ponying up for the jet. Spin a negative into a positive. But does the scandal actually harm Pepsi? Or help them?

Indeed, Byron Sharp suggests in How Brands Grow to never give people a reason not to buy you. But we might be stretching the definition of “a reason”.

People don’t walk through the supermarket debating the morals of brands. In fact, we don’t really make rational decisions at all. For the most part, we’re in zombie mode, not overthinking, grabbing whatever is easiest.

Our brain doesn’t like to think too hard. We like choices, and brands, which are no-brainers.

In that way, brands are like safety nets. Rory Sutherland says “brands don’t exist to make you think a product is excellent, rather to reassure you it won’t be terrible”. If it does what it says on the tin, and if I believe people like me won’t think I’ve made a bad decision, it’s a no-brainer.

Of course, for brands to be a safe choice, they must still tick the right boxes. You don’t want to be famous for unsafe reasons. When Vodafone’s poor network trended in Australia as #vodafail, it became a lot less choosable.

But is the questionable moral behaviour of a company really enough to make a brand unchoosable? And does it affect purchasing behaviour?

How does Volkswagen fare when they’re outed in the 2015 emissions scandal? Four years of consecutive growth (disrupted only by COVID-19).

Likewise, what happens after the Pepsi scandal plays out in the media over years? US market share grows +0.9pp between 1995 and 2000. Can’t have been too harmful, hey?

The best marketing science tells us humans choose brands which easily come to mind. Ehrenberg-Bass Institute calls it ‘mental availability’. Stand out, be noticed, and be recalled when needed.

Years of media coverage over a scandal which isn’t really a scandal, may have only helped Pepsi. And when millions of people spend hours once again with the brand watching the doco, I suspect PepsiCo won’t be too upset.

Of course, the lesson here is not “Do bad things”. As a general rule, people and brands should live by the motto “Don’t be a dick”. And there’s plenty of research suggesting consumers increasingly seek brands which align with their values (although I remain cautious of stated behaviour).

But we must be careful in overstating the extent to which a brand acting like a dick adversely influences buying behaviour. Unless it breaches the ‘safety’ requirement with something truly heinous, some bad PR and a few negative tweets likely help a brand in the long term. Not harm it.

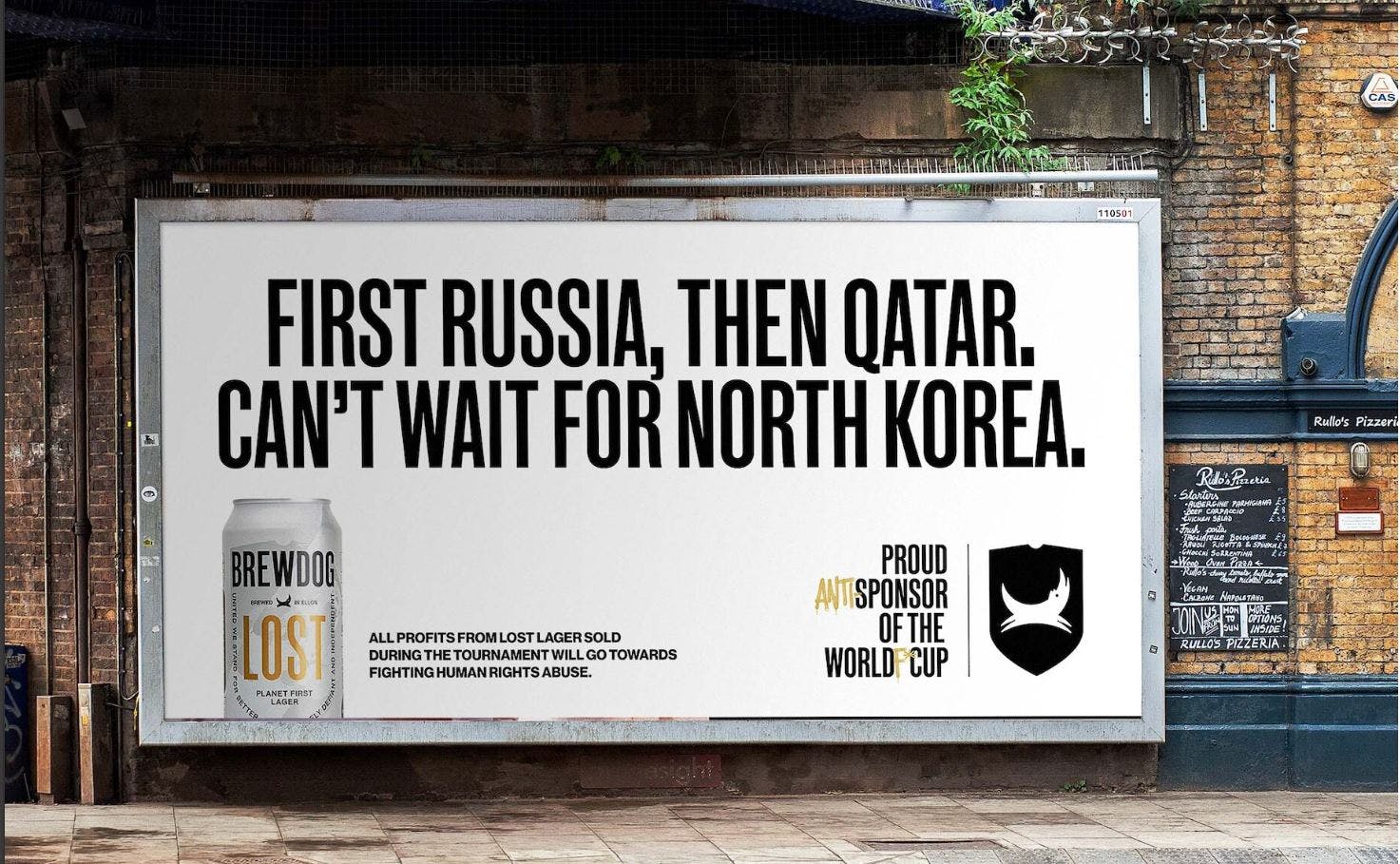

BrewDog has largely built its business on this approach. The latest is a campaign calling out the World Cup. Cue massive criticism once it was revealed they’re still streaming games in their pubs.

This is the BrewDog playbook. Do things which stand out, even if it means some backlash. Maybe, in hope of some backlash. And it works, they grew 31% last year.

It’s a good reminder of Les Binet and Sarah Carter’s research in How Not To Plan: “In over 30 years of evaluation research, we’ve not seen a single example of an ad campaign that’s been shown to have a negative effect on sales. Not one.”

So, what is the lesson? Salience really matters. Do things to grab attention and disrupt. Push your brand into culture. Create work which people talk about and share. Aim for fame.

And yes, do good as well, but don’t forget the getting-noticed part. Heck, maybe even do both.

But there’s no point being right if no one notices.

Zac Martin is a Planning Director at TBWA\Melbourne. This article was originally published in Mumbrella.

Tomas Castro

Posted at February 27, 2023 6:58pm, 27 FebruaryHi Zac! Awesome write-up! Thank you for sharing your thoughts on this. When I saw the documentary, I wondered how this didn’t really impact its growth to now. Great to understand this even better! Cheers!