24 May 2016 Innovation By First

I’ve always been critical of digital gimmicks. Ideas like pizza boxes that turn into projectors or Coke packages that fold into a VR headsets. They are concepts that get a lot of views on YouTube but normal people don’t actually use. They also make really good scam entries into awards.

Maybe I’ve been drinking too much Kool-Aid, and despite my opening paragraph – my skepticism is softening.

Because there is value in the gimmick. Being first to do something builds a perception of innovation and agility. It doesn’t matter if the end user doesn’t use it, because the value of such concepts is the PRability of the video. We see this in a trend toward “consumer-facing case studies”.

Not only do ideas like these build a perception of innovation but can fuel a culture of innovation as well. Fresh gimmicks breed thinking that can be truly effective. No one really wants to order a pizza with an emoji. But Domino’s use and balance these concepts with proper innovation like GPS driver tracking and profit-sharing crowd-sourcing (stuff real people use that drive sales and loyalty).

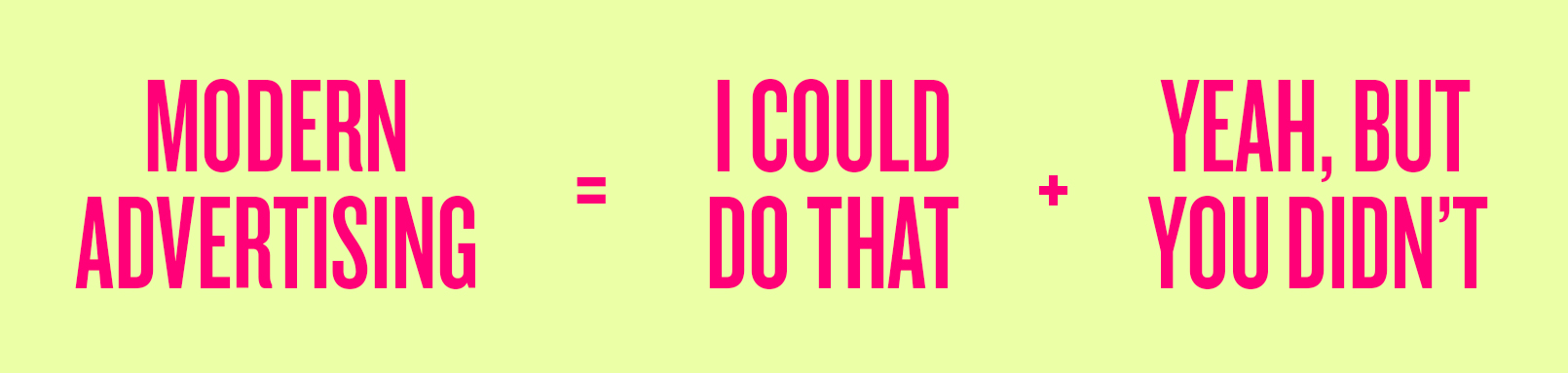

One approach to innovation, and a much cheaper one, is simply getting there first. It won’t disrupt an industry, but it’s not intended to.

As long as your video doesn’t get caught up in the circle jerk that is the marketing tech industry and actually reaches some of your target audience. Ideally in the right country too.

A depressing glimpse into the future.

A depressing glimpse into the future.